Source: http://www.oocities.org/collegepark/pool/1644/marcosera.html

For more than 20 years (Dec. 30, 1965 – Feb. 25, 1986) Ferdinand Marcos ruled the Philippines. He promised to make the nation great again in his inaugural speech of December 30, 1965.

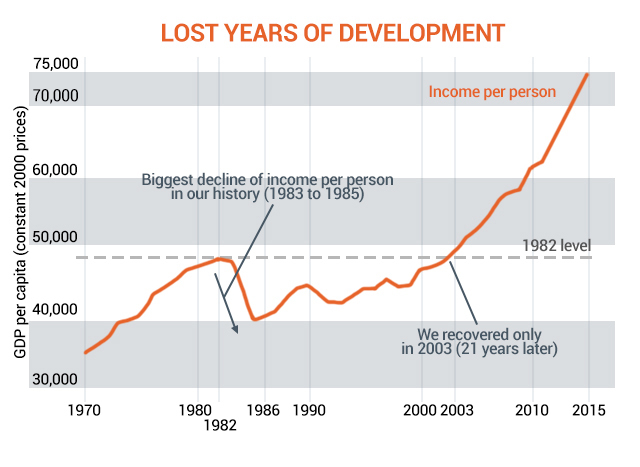

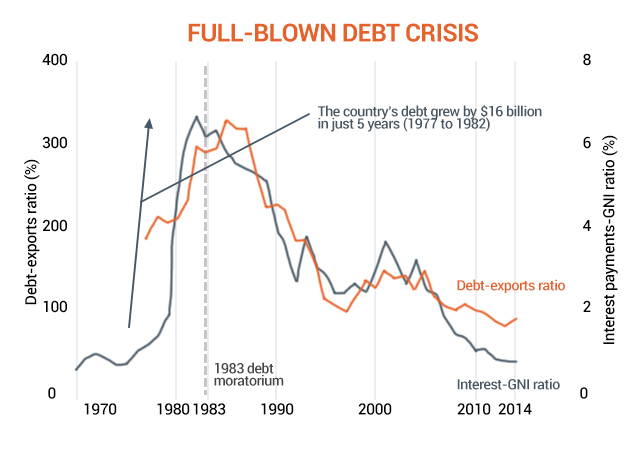

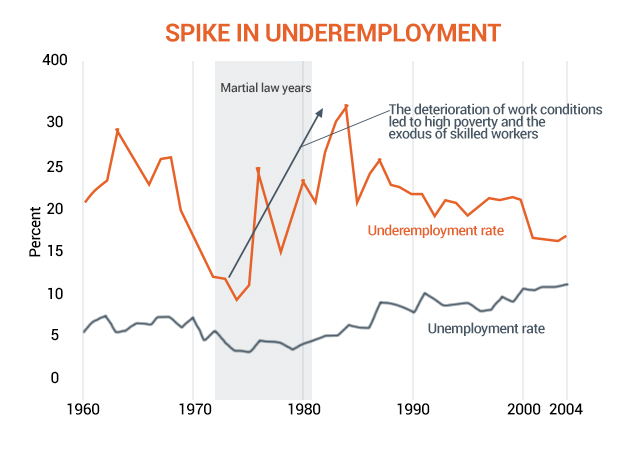

His political venture began with his election to the House of Representatives in 1949 as a Congressman from Ilocos. He became Senate President in 1963. He was married to Imelda Romualdez from Leyte. He ran for President as Nacionalista in 1965 election and won over Macapagal. Elected with Marcos as Vice-President was his NP running mate Fernando Lopez. THE FIRST MARCOS TERM (1965 – 1969) In his first term Marcos tried to stabilize the financial position of the government through an intensified tax collection. He also borrowed heavily from international financing institutions to support a large-scale infrastructure works projects were built. He improved agricultural production to make the country self-sufficient in food, especially in rice. Marcos also tried to strengthen the foreign relations of the Philippines. He hosted a seven-nation summit conference on the crisis in South Vietnam in October, 1966. In support for the U.S. military efforts in South Vietnam, he agreed to send Filipino troops to that war zone. THE SECOND TERM OF MARCOS (1969 – 1972) In November 1969 Ferdinand Marcos and Fernando Lopez were re-elected. They defeated the Liberal Party ticket of Sergio Osmeña, Jr. and Senator Genaro Magsaysay. In winning the election, Marcos achieved the political distinction of being the first President of the Republic to be re-elected. The most important developments during the second term of Marcos were the following: The 1971 Constitutional Convention The Congress of the Philippines called for a Constitutional Convention on June 1, 1971 to review and rewrite the 1935 Constitution. Three-hundred twenty delegates were elected. The convention was headed first by former President Carlos P. Garcia and later by former President Diosdado Macapagal. The Convention's image was tarnished by scandals which included the bribing of some delegates to make them "vote" against a proposal to prohibit Marcos from continuing in power under a new constitution. This scandal was exposed by Delegate Eduardo Quintero. For exposing the bribery attempt, Quintero found himself harassed by the government. The first Papal Visit to the Philippines On November 27, 1970, Pope Paul VI visited the Philippines. It was the first time that the Pope had visited the only Catholic nation in Asia. Huge crowds met the Pope wherever he went in Metro Manila. The Pope left on November 29. The Rise of Student Activism Students protests on the prevailing conditions of the country saddled the second term of Marcos in office. Large throngs of students went out into the street of Manila and other urban centers to denounce the rampant graft and corruption, human rights violation, high tuition fees, militarization and abuses of the military, the presence of the U.S. Military bases and the subservience of the Marcos Administration to U.S. interests and policies. The most violent student demonstration took place on January 1970 when thousands of student demonstrators tried to storm the gates of Malacañang. Six students were killed and many were wounded. This event came to be know as the "Battle of Mendiola". The radical student groups during this period were the Kabataang Makabayan (KM) and the Samahang Demokratikong Kabataan (SDK). The communists took advantage of the situation and used the demonstrations in advancing its interests. The most prominent of the student leaders of this time were Nilo Tayag and Edgar Joson. THE ESTABLISHMENT OF NEW PEOPLE'S ARMY (NPA) Because of the perceived deplorable condition of the nation, the communist movement subdued by President Magsaysay in 1950's, revived their activities and clamor for reform. A more radical group, the Maoists, who believed in the principles of Mao-Tse-Tung (leader of China) took over the communist movement. They reorganized the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and created a new communist guerilla army called the New People's Army (NPA). The communists took advantage of the growing discontent with the Marcos. Administration to increase the number and strength. As a strategy, they actively supported a number of anti-Marcos groups. They infiltrated several student organizations, farmers, laborers and even professionals. The NPA gradually increased its ranks and spread to other parts of the country as far as Mindanao. THE RISE IN ACTS OF VIOLENCE In the early 1970's many of the acts of violence were inspired by the communists. Some, however, were believed to have been planned by pro-Marcos and other terrorist incidents rocked Metro Manila. The bloodiest was the Plaza Miranda Bombing on the night of August 1, 1971 where the Liberal Party had a political rally. Eight persons were killed and over 100 others were injure. Among the senatorial candidates injured were Eva Estrada Kalaw and several of its top officials. Marcos blamed the communists for the tragic incident. He suspended the writ of habeas corpus to maintain peace and other. The suspension was lifted on January 11, 1972. Hundred of suspected subversives among the ranks of students, workers and professionals were picked up and detained by the government. THE PROCLAMATION OF MARTIAL LAW It was believed that the true reason why Marcos declared martial was to perpetuate his rule over the Philippines. The 1935 Constitution limited the term of the President to no more than eight consecutive years in office. The constitution did not say how long martial law should last. The constitution left much about martial law to the President's own judgment. Marcos extended the period of Martial Law beyond the end of his term in 1973. He abolished the Congress of the Philippines and over its legislative powers. Thus, Marcos became a one-man ruler, a dictator. Marcos described his martial law government as a "constitutional authoritarianism". Although the courts remained in the judiciary, the judges of all courts, from the Supreme Court down to the lowest courts, became "casuals". Their stay in office depended on the wishes of the dictator. Under the martial law Marcos disregarded the constitution. For instance, he violated the provision which guaranteed the Bill of Rights (Article III). Upon his orders, the military picked up and detained thousands of Filipinos suspected of subversion. Among them were his critics and political opponents namely Senator Benigno S. Aquino, Jr., Francisco "Soc"Rodrigo, Jose W. Diokno and Jovita R. Salonga. Hundreds of detainees were tortured by their captors. Some disappeared and were never found again. Many were held in military detention camps for years without trial. As a result of the foregoing measured, the crime rate in the country was reduced significantly. People became law-abiding. But these good gains did not last long. After a year of martial law, crime rates started to soar. By the time Marcos was removed from power, the peace and order situation in the country had become worse. This communist insurgency problem did not stop when Marcos declared Martial law. A government report in 1986 showed that the NPAs already numbered over 16,000 heavily-armed guerillas. The NPAs waged a vigorous war against government forces They staged ambuscades and engaged in terrorist activities such as assassination of local officials who were known to be engaged in corrupt activities. The NPA killer squads were called Sparrow Units. They were feared in the areas under their control. They also imposed taxed in their territories. To fight the growing NPA threat, Marcos increased the armed forces to over 200,000 men. He also organized Civilian Home Defense Forces in the rural areas threatened by the NPAs . Several NPA leaders were captured like Jose Ma. Sison, alleged founder of the communist Party in the Philippines; Bernabe Buscayno, the NPA chief, and Victor Corpus, a renegade PC lieutenant. The rampant violation of human rights of the people in the rural areas suspected of being NPA sympathizers, the injustices committed by some government officials and powerful and influential persons, and the continuing poverty of the people were used as propaganda of the NPA in attracting idealistic young people. Even priests and nuns who were witnesses to the oppression of the Marcos dictatorship join the NPAs. One of the priests who joined the NPA was Father Conrado Balweg of the Society of the Divine Word (SVD). He became a rebel folk hero to the ethnic tribes in the Cordilleras in Northern Luzon. As of July 1993, Balweg claimed to reports: "I am still in charge". POLITICAL PARTIES DURING THE MARCOS REGIME In the early years of martial law, political parties were suspended. Political parties resumed only with the election for the Interim Batasang Pambansa on April 7, 1978. It was the first national election under Martial law. The second electoral exercise was the election of local officials held on January 30, 1980. As expected, political parties resurfaced. Those who supported President Marcos formed the Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (KBL) which became in fact anew political party. Its members were from the ranks of the Liberal and Nacionalist parties. The KBL dominated all the elections held during the Marcos era. New political parties emerged to fight the KBL. One such group was the Lakas ng Bayan (LABAN) founded in 1978 by the opposition group headed by former Senator Benigno S. Aquino, Jr. LABAN had a 21-man ticket in Metro Manila for the 1978 IBP elections. The KBL candidates headed by Imelda R. Marcos prevailed in the elections. Aside from LABAN, the other partied organized were the Mindanao Alliance, the Partido Demokratiko ng Pilipinas (PDP), Bicol Saro, Pusyon Bisaya and Pinaghiusa in Cebu. Later on these small political parties united themselved into one umbrella organization that came to be known as the United Nationalist Democratic Organization (UNIDO) headed by former Senator Salvador H. Laurel. The UNIDO had its first electoral exercise in the 1984 Batasan elections. The great majority of the 60 or so opposition lawmakers who were elected in 1984 were UNIDO candidates. ECONOMIC CHANGES UNDER MARCOS To hasten the economic development, President Marcos implemented a number of economic programs. These programs helped the country to enjoy the period of economic growth I the mid-1970's up to the early 1980's. The farmers were given technical and financial aid and other incentives such as "price support". With the incentives given to the farmers, the country's agricultural sector grew. As a result, the Philippines became self-sufficient in rice in 1976 and even became a rice exporter. To help finance a number of economic development projects such as soil exploration, the establishment of geothermal power plants, the Bataan Nuclear Plant, hydro-electric dams, the construction of more roads, bridges, irrigation systems and other expensive infrastructure projects, the government engaged in foreign borrowings. Foreign capital was invited to invest in certain industrial projects. They were offered incentives including tax exemption privileges and the privilege of bringing out their profits in foreign currencies. One of the most important economic programs in the 1980's was the Kilusang Kabuhayan at Kaunlaran (KKK). This program was started in September 1981. Its aim was to promote the economic development of the barangays by encouraging the barangay residents to engage in their own livelihood projects. The government's efforts resulted in the increase of the nation's economic growth rate to an average of six percent to seven percent from 1970 to 1980. The rate was only less than 5 percent in the previous decade. The Gross National Product of the country (GNP) rose from P55 billion in 1972 to P193 billion in 1980. Another major contributor to the economic growth of the country was the tourism industry. The number of tourists visiting the Philippine rose to one million by 1980 from less than 200,000 in previous years. The country earned at $500 million a year from tourism. A big portion of the tourist group was composed of Filipino balikbayans under the Ministry of Tourism's Balikbayan Program which was launched in 1973. Another major source of economic growth of the country was the remittances of overseas Filipino workers. Thousands of Filipino workers found employment in the Middle East and in Singapore and Hongkong. These overseas Filipino workers not only helped ease the country's unemployment problem but also earned much-needed foreign exchange for the Philippines. FOREIGN-RELATIONS POLICY UNDER MARCOS REGIME In 1976 President Marcos announced to the Filipino people his policy of establishing relations with communist countries such as the People's Republic of Chine (june 9, 1975) and the Soviet Union (June 2, 1976). Relations with the United States was modified. It was no longer based on the "sentemental ties" but on mutual respect for each other's national interest. Thus, the military and economic agreements between U.S. and the Philippines were amended to reflect this new relationship. In the amendments to the RP-U.S. Military Bases Agreement of 1947, the U.S. acknowledged the sovereignty of the Philippines over the American military bases in the country (Subic and Clark). These bases would have a Filipino commander and would fly the Philippine flag. IN addition, the U.S agreed to pay rentals to the Philippines for the use of the bases. Marcos established closer ties with the Asian countries. The Philippines became a leading member of the Third-World – the collective name for the developing countries at that time. The Philippines actively participated in such world conferences as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) meeting held in Nairobi, Kenya, in 1976 and in the International Meeting on "Cooperation and Development held by the heads of 21 nations in Cancun, Mexico, in 1981. Marcos took his oath of office on June 30, 1981 at the Luneta Park for a six-year term ending in 1987. On that occasion Marcos announced the establishment of a "New Republic of the Philippines". The lifting of Martial Law After implementing the program of development, Pres. Marcos issued Proclamation NO. 2045 on January 17, 1981, lifting Martial Law. Martial Law lasted for eight years, 3 months and 26 days. Mr. Marcos lifted Martial law to show to the Filipinos and the world that the situation in the Philippines was already back to normal. The government had already been functioning smoothly under the 1973 Constitution. Despited the lifting of Martial law, however, Marcos remained powerful and practised authoritarian rule. The Presidential Election of 1981 Marcos called for a presidential election to be held on June 16, 1981. In this election he had Alejo Santos of the Nacionalista Party as opponent. Former Senator Benigno Aquino, Jr. was then living in exile abroad and could not run for presidency. The Liberal Party did not take part in the election. It was a runaway victory for Marcos who obtained 88% of the total votes cast. It was believed that Marcos won in the 1981 election because he was in full control of the situation. Marcos took his oath of office on June 30, 1981 at the luneta Park for a six-year term ending in 1987. On that occasion Marcos announced the establishment of a "new" Republic of the Philippines. THE RETURN AND ASSASINATION OF BENIGNO S. AQUINO, JR. When martial law was proclaimed, the first politician to be arrested by the military on order of Ferdinand Marcos was Benigno S. Aquino, Jr. Aquino, a popular political leader, spent nearly eight years in a military detention cell at Fort Bonifacio. In 1980, Marcos allowed Aquino to leave the country to enable him to undergo an emergency heart bypass operation in the United States. When Aquino decided to come home in 1983, the government tried to stop him, claiming that there were some people who wanted to kill him. He was asked to postpone his return. But Aquino persisted, and by using fake travel documents, he was able to fly back to the Philippines. The assassination of Aquino was reported to have awakened the Filipinos to the evils of Marcos as a dictator. Millions of Filipinos who sympathized with Aquino bereaved family, joined the funeral march to mourn for the death of an intelligent leader and to express their feelings against Marcos. The demonstrations were participated by different sectores, namely students, workers, farmers, businessmen, professionals and religious (nuns, priests and seminarians). Many militant and cause-oriented groups were the August Twenty-One Movement (ATOM), Justice for Aquino, Justice for All (JAJA), Bagong Alyansang Makabayan (BAYAN). The Aquino assassination gave Marcos a bad image abroad, Public opinion in the United States went against Marcos. President Reagan of the United States cancelled his state visit to the Philippines. On October 14, 1983, President Marcos issued PD 1886 creating a five-man independent body to investigate the Aquino assassination. Headed by Mrs. Corazon Juliano Agrava, a retired Court of Appeals Justice, the investigation body came to be known as the Agrava-Fact-Finding Board (AFFB). The other members of the board were businessman Dante Santos, labor leader Ernesto Herrera, lawyer Luciano Salazar, and educator Amado Dizon. The members of the AFFB, however, identified 25 military men and a civilian as participants in the plot. Those identified include AFP Chief of Staff General Fabian C. Ver, Jam. General Prospero Olivas of the PC Metropolitan Command (METROCOM) and Gen. Custodio. President Marcos referred the two reports to the Sandiganbayan for trial. The trial began in Feb. 1985, and was presided over by Sandiganbayan Presiding Justice Manuel Pamaran. This trial became known as "Trial of the Century". On December 2, 1985, the Sandiganbayan handed down its decision. The tribunal ruled that the 26 accused were innocent and that it was Galman who was hired by the communist who killed Aquino. THE DECLINE OF THE ECONOMY As the investigation and trial of the Aquino Assassination was going on, the Philippine economy was having hard times. There was a slow down of economic activities caused largely by high price of oil. The Philippine traditional exports such as sugar and cocunut oil were experiencing a price decline in the world market. The government was forced to borrow more money from the International Monetary Fund to help keep the economy going. The foreign debt of the Philippines reached $26 billion. A big portion of the annual earning of the country was allocated to the payment of annual interest on loans. The tourism industry suffered a great decline after the Aquino Assassination. The wave of anti-Marcos demonstrations in the country that followed drove the tourists away. In addition, the political troubles hindered the entry of foreign investments. Foreign banks also stopped granting loans to the Philippine government. Foreign creditors started demanding payment of the debts which were already past due. Without an adequate supply of foreign exchange, the industry sector could no longer import raw materials needed in production. Many factories had to close shop of cut their production because of the difficulty of obtaining raw materials. Many workers were laid off. Marcos tried to launch a national economic recovery program. He nogotiated with foreign creditors including the International Bank for reconstruction and Development, World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), for a restructing of the country's foreign debts – to give the Philippines more time to pay the loans. Marcos launched the Sariling Sikap, a livelihood program, in 1984. He ordered the cut in government expenditure to be able to save money for financing the livelihood program. Despite the recrovery program, the economy continued to decline. A negative economic growth was experienced in the country beginning in 1984. The failure of the recovery program was due to the lack of credibility of Marcos and the rampant graft and corruption in the government. Many officials went on stealing the people's money by millions through anomalous transactions. Marcos himself spent large sums of government funds to help the candidates of the KBL to win. THE SNAP ELECTION OF 1986 As the economy continued to decline, the IMF, World Bank, the United States and the country's foreign creditors pressured Marcos to institute reforms as a condition for the grant of additional economic and financial help. Rumors then spread about the possibility of a snap presidential election. The rumors turned to be true because in November 1985, Marcos announced that there would be a snap presidential election. Marcos said that he needed a new mandate from the people to carry out a national economic recovery program successfully. The Batasang Pambansa enacted a law scheduling the election on February 7, 1986. The divided opposition had the problem of choosing a candidate to fight Marcos. There were several opposition leaders who aspired to run for president, one of them being former Senator Salvador "Doy" H. Laurel who was nominated in June 1985 by the UNIDO to be its presidential candidate in any future presidential election. But none of them could unite the opposition. A majority of the opposition and other anti-Marcos groups proposed instead that Mrs. Corazon C. Aquino be made the common opposition candidate for president. Due to a growing nationwide clamor for her to lead the opposition, Aquino agreed to run if Marcos would call for an election and at least one million people would sign a petition urging her to run for president. After the announcement of snap election by Marcos, the Cory Aquino for President Movement (CAPM), organized by Joaquin "Chino" Roces, was able to solicit more than one million signatures nationwide asking Mrs. Aquino to run against Marcos. Upon the advice of Jaime Cardinal Sin, the Archbishop of Manila, former Senator Salvador Laurel of the UNIDO Party decided to sacrifice his presidential ambition for the sake of unity of the opposition by agreeing to run as Corazon Aquino's vice-presidential candidate. The campaign period was from Dec. 11, 1995 to Feb. 5, 1986. The two rival political camps had their slogans and symbols. The LABAN Party of Cory Aquino had yellow as the symbolic color while the KBL of Marcos had red. The Aquino'' campaign slogan was "Tama na, Sobra na, palitan na!" The Marcos slogan was "Marcos pa rin!" Aquino had her "L" sign while Marcos had his "V" sign. Corazon Aquino campaigned on the issue of ending the Marcos dictatorship and the restoration of freedom, justice and democracy. She charged Marcos with impoverishing the nation by allowing his family and cronies to rob the Filipinos of their wealth though illegal transactions. She also denounced the gross violations of human rights of the Marcos regime. She promised to give justice to the victims of harassment and abuses by the government officials. President Marcos accused Mrs. Corazon Aquino of being a communist herself and said that her husband, Ninoy Aquino, was one of the founders of the Communist Party of the Philippines. He warned that an Aquino victory would pave the way for communist rule in the Philippines. Marcos also criticized Aquino for her lack of experience in government. IN the election campaign, Marcos said that he favored the retention of the U.S. Military Bases. On the other hand, Mrs. Aquino said whe would let the U.S. Military stay until 1991 when the Military Bases Agreement (MBA) expired. Mrs. Aquino also accused Marcos of being responsible for her husband's assassination. She also disclosed that Marcos was a fake World War II hero. THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OF 1986 On February 7, 1986, election day, about 20 million registered voters cast their votes in som 86,000 election precincts throughout the country. It was the most historic in the history of the 3rd republic. It was reported to be the "most controversial and confusing election" ever held in the Philippines, the "most internationally publicized election", and the "most fraudulent election" in the Philippine history. Marcos resorted to massive vote buying to ensure his victory. KBL leaders in many areas used armed goons to terrorize the voters. There were instances of ballot box snatching. Flying voters were used. Election returns were falsified or altered. So widespread was the cheating that the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) in a statement issued a week after election, strongly condemned the conduct of the election. The CBCP described the election as "unparalleled in its fraudulence". The Batasang Pambansa convened itself to make an official canvass of the election returns and to proclaim the winners. Based on the certificates of the canvass submitted to it by the Comelec registrars of 143 provinces, cities, and election districts, the Batasan on Feb. 15, 1986 proclaimed Ferdinand Marcos and Arturo Tolentino as the duly elected president and vice-president , respectively. The official Batasan tabulation showed that Marcos obtained 10,807,197 votes as against Aquino's 9,291,715 votes. The Batasang Pambansa, which was controlled by the KNL, went on with the canvassing amidst the objections of the opposition members. The opposition MPs pointed out that there were irregularities in most of the certificates of canvass. The fraudulent election Feb. 7, 1986 destroyed the image of President Marcos and his government abroad. Based on the reports of foreign newsmen and on what they saw on television, many people in the Philippines and abroad felt that Marcos was not the legitimated President of the Philippines. They believed that it was Corazon Aquino who won the presidency. As a result, except for the Soviet Union, not one foreign country congratulated Marcos. The fraudulent election weakened American support for the Marcos Regime. After receiving the report of Senator Lugar who headed the U.S. election observer team in the Philippines, President Reagan said that "the fraudulent election casts doubts on the legitimacy of Marcos' re-election. Mrs. Corazon Aquino, believing that she won, refused to accept the election of Marcos. So did the Catholic Church and many other groups which issued strong statements condemning the fraudulent election. On Feb. 16, 1986, Corazon Aquino launched a civil disobedience nationwide at Luneta. The Philippines on the Eve of the EDSA Revolution In the country, particularly in Metro Manila, political tension was rising to new heights. The Aquino civil disobedience movement rapidly gained heights and strengths. Students and teachers in many colleges and universities boycotted their classes to protest the fraudulent. February 7 election. Worker's groups planned for a general labor strike throughout the nation. In the face of these events which threatened his dictatorial regime, Marcos began to issue warnings. He threatened to use his extra-ordinary powers to crush the strike movement. And he gave indications to impose martial law again. In fact he had already prepared a plan code named "Everlasting". The plan called for sending out soldiers loyal to his regime into the streets of Metro Manila to spread terror and violence. They would be in civilian clothes and would pretend to be Aquino followers. This would be used by Marcos as an excuse to impose martial law again in the country. Like what he did in 1972, Marcos would have the military arrest and detain the leaders of the opposition, including those among the clergy and in the armed forces who opposed him. But before he could carry out his plan, the EDSA Revolution of 1986 broke out. Plans for a Military Coup De'etat This movement was started in March 1985 by a group of officers who were graduated of the Philippine Military Academy. Its main aim was to work for reform in the armed forces. Just like the other branches of the government, the AFP was riddles with graft and corruption, favoritism and other anomalies that demoralized the decent members of the military. RAM wanted the restoration of professionalism in the military so that the AFP could regain its honor and pride. A reformed AFP, the movement's organizers believed, would be able to fight more effectively the growing communist threat in the Philippines. Minister of Defense Juan Ponce Enrile secretly sympathized with RAM. The members of the RAM came to be know as reformists. When the RAM realized that Marcos had discovered their plot they sought refuse at the Ministry of National Defense building at Camp Aguinaldo in Quezon City. Enrile took command of the military rebellion. General Fidel Valdez Ramos, the AFP vice-chief of staff and PC chief, sided with Enrile and the reformists and took over control of the Philippine Constabulary Headquarters in Camp Crame which is located across Epifanio delos Santos Avenue (EDSA) from Camp Aguinaldo. OUTBREAK OF THE 1986 REVOLUTION They said that the Marcos did not win the February 7 snap Presidential election and therefore did not have the mandate of the people. |